Systematic review on awake surgery for lung metastases

Introduction

Although many surgeons perform lung metastasectomy, the role of surgery in the treatment of lung metastases is not well established (1-3). Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to perform metastasectomy is becoming more common (4-7). In recent years some authors initiated an awake surgery program also to perform lung metastasectomy (LM) (8,9), and a further improvement seems to be represented by the use of uniportal awake approach (10,11).

Clinical scenario and results

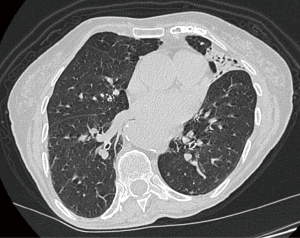

An 85-year-old woman presented to our clinic. Past medical history included rectal carcinoma, arrhythmia, motor neuron disease, herniated discs and chronic cerebrovasculopathy. The CT-scan revealed a nodule, with the maximum diameter of 4 mm in the lingula close to an area of consolidation (Figure 1). The PET-CT scan showed a highly avid lesion. Preoperative studies include: blood tests, arterial blood gases, spirometry and cardiological examination. Cardiological and neurological history were considered by the anesthetists as a contraindication to general anesthesia, then the only possible option was considered the removal of the small nodule under awake surgery.

Anesthesia and operative technique

The patient was continuously monitored during the procedure with pulse oximeter, electrocardiogram, invasive blood pressure, bispectral index (BIS) and arterial blood gases. Verbal numeric scale (VNS) was used intraoperatively to evaluate the pain. Midazolam 1.5 mg and Fentanyl 50 mcg were administered to the patient. The aim was to keep BIS between 75 and 85. Patient kept spontaneous breathing with SpO2 95–96% (nasal cannula FiO2 30%). Intraoperative arterial blood gases were normal. One gram of Paracetamol was administered as analgesic. At the end of the surgical treatment the patient showed normal vital signs, BIS 98 and VNS was 0.

The surgical-team included the primary surgeon, assistant doctor and scrub nurse. The surgeon operated facing the back of the patient. The first assistant was on the opposite side of the operating table. Two monitors were positioned opposite to the surgeon and to the assistant and nurse. The position of the patient was the standard posterolateral decubitus. A 3-cm skin incision was made over the 5th intercostal-space and at the level of the mid-axillary-line. The target intercostal space was chosen on the basis of the CT-scan, and a 4 steps local anesthesia was performed as previously described (12). There were some adhesions, the chest was entered, and the index finger used to palpate the lung. When the nodule was palpated, the lung was easily grasped and the nodule subsequently resected using an endo-stapler extracorporeally (Figure 2) (14). The specimen was divided and sent for microbiological and pathological examinations. A chest drain was inserted through the incision. A chest-radiograph was taken in the recovery room. The patient was observed for 3 hours prior to her transfer to the high dependency unit. She was discharged home on the 3rd post-operative day and the patient is well 9 months after the surgery.

Methods and literature search strategy

Taking a cue from the clinical scenario a review on PubMed was conducted. The Following search terms were used to retrieve potentials published articles from PubMed: “awake surgery” or “awake lung surgery” or “awake surgery for lung metastasectomy” or “non-intubated lung metastasectomy” or “awake surgery for pulmonary metastasectomy” or “non-intubated pulmonary metastasectomy” or “awake surgery for lung metastases” or “non-intubated lung metastases” or “awake surgery for pulmonary metastases” or “non-intubated pulmonary metastases”.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

We considered all published articles from 2000 to April 2017, which reported on at least sufficient data to be eligible. The literature search was limited to articles in English. We evaluated the reports’ quality from the titles and abstracts. The references of all eligible studies were checked for identification of additional studies to be included in the review. No attempt was made to locate unpublished material. Reviews and teaching articles which contributed no data for analysis were excluded. Case reports and small series on pediatric patients were also excluded. The research was limited to studies on humans and adults.

Results

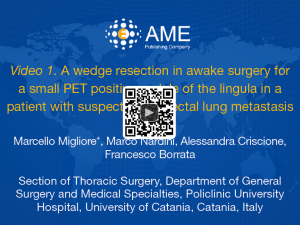

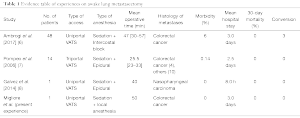

Our literature search yielded 5,295 studies, of which 3 fulfilled our inclusion criteria (8,9,15). From them, only 2 study presented statistical analysis data (Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric data and Kaplan-Meier for the survival) (Table 1). A flow chart of our search results according to PRISMA guidelines is shown in Figure 3. Data and outcomes of interest for this review were type of anesthesia, type of access, mean operative time, histology of metastases, conversion rate, 30-days mortality, composite outcome (morbidity) and mean hospital stay. The objective of these studies was to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and benefits of the awake surgery for the treatment of lung metastases. Moreover, of the seven studies on awake surgery for LM, four were from the same group.

Full table

Discussion

Minimally invasive surgery represents an important evolution in thoracic surgery, and it is now well known that it provides improvement in postoperative pain, average hospitalization and related costs.

Awake surgery may represent a further step forward, and it is to be considered suitable for selected patients, with many advantages. In general, the absence of general anesthesia means early post-operative pulmonary re-expansion, faster recovery and a decrease in hospitalization time (8). During awake surgery, the iatrogenic pneumothorax allows a sufficient lung collapse, allowing a proper operative field. Air trapping due to lung isolation with double lumen tube is avoided. Moreover, the presence of spontaneous breathing and mobility of the diaphragm counteract the possibility of a mediastinal shift (9).

Nowadays, surgical indication for awake surgery for LM is very strict. Kiss et al. performed only 2 lung metastasectomy in awake surgery out 716 (0.27%) patients requiring thoracic surgery (16). Certainly, before an awake operation for lung metastases a multidisciplinary meeting is necessary as the presence of multiple nodules, the extension and the number of PM should be carefully studied (17,18). Of note, we advocate that when uniportal surgery is preferred the site of skin incision should be carefully chosen on the basis of the preoperative CT-scan. We generally perform the incision above the target lesion.

The systematic review revealed weak data. Two papers have been written by the same group (8,9). Ambrogi et al. (8) and Pompeo et al. (9) compared awake metastasectomy with a control group of standard VATS metastasectomy reporting a significant difference in operating-room time, hospital stay and estimated costs (P<0.05) in favor of the awake surgery group. Decreasing of operating times allows to increasing the number of daily procedures and further decreasing the costs (8). Moreover, awake surgery for lung metastasectomy demonstrated to cause significantly less immunological and inflammatory response compared to procedures under general anesthesia (19).

The main criticisms are twofold. The first is regarding the small access’ size which limits palpation of the pulmonary parenchyma and prevent further search of any unexpected nodules. This problem may be more significant during awake surgery than traditional VATS. In fact, during awake surgery there is the surgeon tendency to reduce even further the length of skin incision and the operative time. Despite this, Pompeo et al. stated that there is no difference between the awake surgery group and the control group (VATS metastasectomy with general anesthesia) in terms of the number of nodules palpated and resected (8). Moreover, recent imaging studies and the combined use of high resolution chest CT-scan and PET scan reduce the risk of leaving ‘un-palpated nodules’ in situ. The second could be the difficulty to perform a suitable lymphadenectomy which is important to stage correctly the disease, and to predict the prognosis (20).

Conclusions

Awake surgery for LM is a possible choice for selected patients when the general anesthesia or the intubation is contraindicated. Although there is “encouraging” evidence concerning awake LM, its quality is still very weak to confirm the effectiveness of this surgical strategy. Therefore, better evidence, preferably in the type of a randomized controlled trial, is necessary to clearly evaluate the benefit of this novel therapeutic approach. Also, it is mandatory to establish some standardized criteria for surgical indication. The initial reported positive results can drive further research in this direction, but caution is necessary.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery for the series “Non-intubated Thoracic Surgery”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/vats.2017.09.06). The series “Non-intubated Thoracic Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. MM served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series and serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery from Mar 2017 to May 2019. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Treasure T, Milošević M, Fiorentino F, et al. Pulmonary metastasectomy: what is the practice and where is the evidence for effectiveness? Thorax 2014;69:946-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunning J. A view of the Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Colorectal Cancer (PulMiCC) trial from the coalface. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:798-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Milošević M, Lees B, et al. Finding the evidence for pulmonary metastasectomy in colorectal cancer: the PulMicc trial. Future Oncol 2015;11:15-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perentes JY, Krueger T, Lovis A, et al. Thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary metastasis: current practice and results. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2015;95:105-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Perentes JY, Ris HB, et al. Survival and Local Recurrence After Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lung Metastasectomy. World J Surg 2016;40:373-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Criscione A, Calvo D, et al. Wider implications of video-assisted thoracic surgery versus open approach for lung metastasectomy. Future Oncol 2015;11:25-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carballo M, Maish MS, Jaroszewski DE, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) as a safe alternative for the resection of pulmonary metastases: a retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;4:13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambrogi V, Sellitri F, Perroni G, et al. Uniportal video-assisted thoracic surgery colorectal lung metastasectomy in non-intubated anesthesia. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:254-261. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pompeo E, Mineo TC. Awake pulmonary metastasectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:960-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Calvo D, Criscione A, et al. Uniportal video assisted thoracic surgery: summary of experience, mini-review and perspectives. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:E378-80. [PubMed]

- Migliore M. Efficacy and safety of single-trocar technique for minimally invasive surgery of the chest in the treatment of noncomplex pleural disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;126:1618-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Giuliano R, Aziz T, et al. Four-step local anesthesia and sedation for thoracoscopic diagnosis and management of pleural diseases. Chest 2002;121:2032-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Nardini M, Criscione A, et al. A wedge resection in awake surgery for a small PET positive nodule of the lingula in a patient with suspected colorectal lung metastasis. Asvide 2017;4:435. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/articles/1751

- Migliore M, Criscione A, Parfrey H. A hybrid single-trocar VATS technique for extracorporeal wedge biopsy of the lingula in patients with diffuse lung disease. Updates Surg 2012;64:223-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galvez C, Bolufer S, Navarro-Martinez J, et al. Awake uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic metastasectomy after a nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:e24-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiss G, Claret A, Desbordes J, et al. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia for awake thoracic surgery in severely dyspnoeic patients excluded from general anaesthesia. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:816-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Jakovic R, Hensens A, et al. Extending surgery for pulmonary metastasectomy: what are the limits? J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:S155-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Migliore M, Gonzalez M. Looking forward lung metastasectomy-do we need a staging system for lung metastases? Ann Transl Med 2016;4:124. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mineo TC, Sellitri F, Vanni G, et al. Immunological and Inflammatory Impact of Non-Intubated Lung Metastasectomy. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18:E1466 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Call S, Rami-Porta R, Embún R, et al. Impact of inappropriate lymphadenectomy on lung metastasectomy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Surg Today 2016;46:471-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Migliore M, Borrata F, Nardini M, Timpanaro V, Astuto M, Fallico G, Criscione A. Systematic review on awake surgery for lung metastases. Video-assist Thorac Surg 2017;2:70.